Am Law 100 2022 Forum

Forum rules

Anonymous Posting

Anonymous posting is only appropriate when you are revealing sensitive employment related information about a firm, job, etc. You may anonymously respond on topic to these threads. Unacceptable uses include: harassing another user, joking around, testing the feature, or other things that are more appropriate in the lounge.

Failure to follow these rules will get you outed, warned, or banned.

Anonymous Posting

Anonymous posting is only appropriate when you are revealing sensitive employment related information about a firm, job, etc. You may anonymously respond on topic to these threads. Unacceptable uses include: harassing another user, joking around, testing the feature, or other things that are more appropriate in the lounge.

Failure to follow these rules will get you outed, warned, or banned.

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Am Law 100 2022

Is there any way for someone to post the full Am Law 100 list for 2022 that just got put up? I don't have subscriber access but interesting in seeing the numbers.

-

Hick4Life

- Posts: 4

- Joined: Wed Sep 16, 2020 2:34 pm

Re: Am Law 100 2022

I also am not subscribed but I am able to use the tables linked here (https://www.law.com/americanlawyer/2022 ... 0326122259) to see everything.

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

LOL, what is up with this corny "Premier League" vs. "Championship League" concept AmLaw cooked up this year? Also confused by the practice cachet categories — though I guess I approve of them ranking Milbank as "preeminent," above (e.g.) Weil and Cleary in the lower "prestige" category.

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

That Paul HasTTTings rankingAnonymous User wrote: ↑Tue Apr 26, 2022 5:41 pmLOL, what is up with this corny "Premier League" vs. "Championship League" concept AmLaw cooked up this year? Also confused by the practice cachet categories — though I guess I approve of them ranking Milbank as "preeminent," above (e.g.) Weil and Cleary in the lower "prestige" category.

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

Doesn't work unless subscribedHick4Life wrote: ↑Tue Apr 26, 2022 12:29 pmI also am not subscribed but I am able to use the tables linked here (https://www.law.com/americanlawyer/2022 ... 0326122259) to see everything.

Want to continue reading?

Register now to search topics and post comments!

Absolutely FREE!

Already a member? Login

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

Can you select the table and hit ctrl cHick4Life wrote: ↑Tue Apr 26, 2022 12:29 pmI also am not subscribed but I am able to use the tables linked here (https://www.law.com/americanlawyer/2022 ... 0326122259) to see everything.

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

Can someone post a top 10 on each of the metrics (or at least a couple). I could only find gross rev on ATL

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

PPEPAnonymous User wrote: ↑Tue Apr 26, 2022 6:27 pmCan someone post a top 10 on each of the metrics (or at least a couple). I could only find gross rev on ATL

Wachtell $8,400,000

Kirkland $7,388,000

DPW $7,010,000

S&C $6,366,000

P, W $6,162,000

STB $5,980,000

Cravath $5,803,000

Quinn $5,746,000

Latham $5,705,000

Cahill $5,533,000

Rest are: Weil, Skadden, Milbank, Deb (all 5 million plus). Paul Hastings, Cleary, Gibson, Cadwalader, K&S, Ropes, Fried Frank, Dechert, Cooley: all 4 million plus.

RPL

Wachtell 3,860,000

S&C 2,215,000

Cravath 2,035,000

Kirkland 1,997,000

Ropes & Gray 1,950,00

DPW 1,923,00

STB 1,913,000

Quinn 1,839,000

Skadden 1,838,00

P, W 1,836,000

10-25 is: Cahill, Latham, Fenwick, Deb, Milbank, Proskauer, Fried Frank, Gibson Dunn, Paul Hastings, Weil, Cooley, Wilmer, Goodwin, Sidley, Cadawalader (Cahill at 1,818,000 and Cadwalader at 1,474,00)

Revenue

Revenue is kinda dumb so just giving: Kirkland (6 billion), Latham (5 billion), DLA, Baker, Skadden (3 billion).

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

Premier League Table

1. Watchtell

2. Davis Polk

3. Simpson Thacher

4. Kirkland

5. Sullivan & Cromwell

6. Latham

7. Debevoise

8. Paul Weiss

9. Cahill

10. Ropes & Gray

11. Paul Hastings

12. Milbank

13. Weil

14. Cravath

15. Fenwick

16. Skadden

17. Fried Frank

18. Quinn Emmanuel

19. Gibson Dunn

20. Cleary

NP. Cooley

NP. Goodwin

Championship League

23. Sidley Austin

24. Willkie Farr

25. King & Spalding

26. Proskauer Rose

27. Dechert

28. McDermott

29. Wilson Sonsini

30. Cadwalader

31. Vinson & Elkins

32. White & Case

33. Wilmer

34. Schulte

35. Alston & Bird

36. Akin Gump

37. Winston & Strawn

38. Orrick

39. Kramer Levin

40. Covington

41. O'Melveny

42. Sheppard Mullin

43. Morgan Lewis

44. Pillsbury

45. Shearman

Full Article:

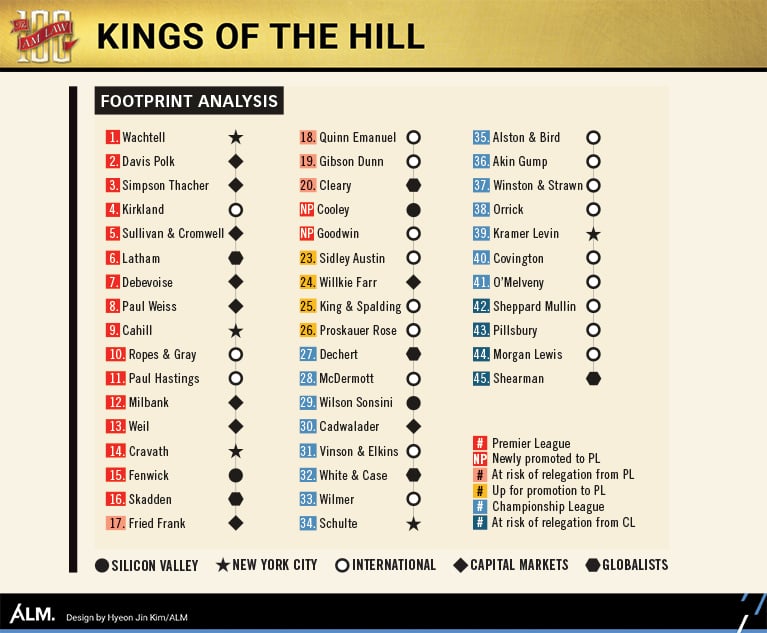

Kings of the Hill: Power Ranking the Am Law 100 Based on Momentum, Profit and Prestige

As firms fight for Big Law standing, a segmentation analysis of the Am Law 100 reveals shifts in the pecking order.

By Jae Um

For most casual observers, Kirkland & Ellis and Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz represent the pinnacle of success in Big Law. Kirkland capped off a fairytale decade with $6.04 billion in revenue in 2021 and $7.4 million in profits per equity partner. Wachtell retained pole position—for the 15th year in a row—in per-lawyer metrics with $3.9 million in revenue per lawyer and $8.4 million in PEP.

But the two firms take starkly different routes to prestige and profit. Kirkland is a powerhouse megafirm with head count exceeding 3,000, a two-tier partnership and the most aggressive growth strategy in the business. Wachtell has remained small and mighty, with fewer than 300 lawyers in a single office in New York, zero nonequity partners, and a lockstep compensation system.

Since its inception, the Am Law 100 has never been a homogenous group. A prevailing philosophy of manifest destiny has led many firms to expand and consolidate, creating a cadre of self-described full-service national firms. Most firms rule the roost in their own backyards, but an increasing number are expanding aggressively for international reach. Specialists like Littler Mendelson and Fish & Richardson are listed alongside global platforms like Baker McKenzie and DLA Piper.

Are these firms really in the same business? What do these diversifying strategies tell us about the direction of travel and varying pathways to success in today’s legal market?

Power Rankings: Momentum, Profit and Prestige

To help make sense of an increasingly frenetic and complex legal market, Six Parsecs constructed a scoring model for the 2022 Am Law 100. The methodology is designed to measure momentum as well as profit and prestige, with emphasis on profitable growth and upward trajectory in key metrics.

Modeled after the English Premier League, these power rankings define two divisions. The core model places 20 firms in the Premier League, giving us a roster of highly recognizable global elites alongside a few surprising names that underline the emerging influence of private capital as well as the dominance of technology and life sciences at the world’s most prestigious firms.

The next tier of firms—what we’ll call the Championship League—includes those currently winning in their regions and categories. Like the EPL, the model flags promotion and relegation candidates to better reflect the fluidity of legal business and volatility we’ve observed in legal markets in the past decade—reminding firms that position is not destiny, neither success nor failure is eternal, and we always live to fight another day.

The intent of this study is to reflect the zeitgeist of the industry in a watershed year. These league tables highlight the firms that are competing most fiercely to move upmarket in an increasingly volatile environment.

Which firms are on the rise? Who’s winning the battle for talent? Is all growth good? What commonalities do successful firms share? Which strategies and tactics are unique to a certain cohort of firms and which are universally applicable?

These are the questions that are often top of mind for law firm leaders. To place greater context around these power rankings, we’ve also integrated analysis of footprint, practice mix and sector focus. Based on this analysis, we delve into the strategy playbooks defining competition today.

Bigger Isn’t Better

The ascendancy of Kirkland and Latham & Watkins has fueled a common narrative that getting bigger is a positive. The sequel narratives that follow are troubling: growth is necessary and growth equals success.

Get More Information Get More Information

A quantitative analysis of the Am Law 100 over the last 10 years indicates little to no correlation between size and financial performance. An analysis of 45 firms that comprise “Everyone Else” in these rankings shows that firms with fewer than 500 lawyers outperformed larger firms on both RPL and average partner compensation. On balance, larger firms are harder to manage, and the data suggests that indiscriminate pursuit of head count growth is a risk indicator. The largest firms by head count are often firms with a global footprint in emerging markets with challenging price pressures.

Size is not what sets Kirkland and Latham apart from the pack. Foresight, boldness and focus are far more controlling attributes that have allowed these two firms to establish and hold dominant positions. The reshaping of global capital markets away from public markets to private equity and the increasing sophistication and specialization of debt instruments created huge opportunities for law firms. Despite—or, perhaps, because of—the length and depth of relationships between the bankers and lawyers of Wall Street, Kirkland and Latham got the jump on private equity giants Blackstone, KKR, TPG and the Carlyle Group.

On a five-year basis, the Am Law 100 firms with most aggressive head count growth comprise a mixed bag. A few rising stars like Goodwin Procter and Cooley have managed to grow while moving upmarket and improving profitability. Down-market players like Lewis Brisbois Bisgaard & Smith and Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani have both grown head count by over 40% with uneven results on partner compensation, with RPL hovering around the $450,000 to $500,000 range and CAP in the $350,000 to $425,000 range.

At the other end of the spectrum, longstanding powerhouse Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom has contracted head count by 10% in the last decade while posting consistently strong performance in profitability. In fact, Skadden is the only firm that has managed to post consistent gains in partner compensation that beat inflation every single year since the Great Recession. Sullivan & Cromwell and Cravath, Swaine & Moore have both maintained essentially the same head count over the past five years while achieving outstanding gains in RPL and PEP.

It is true that certain size thresholds offer advantages to help diversify practice mix and to establish sufficient operating scale to make critical infrastructure investments. Up and down our league tables, the sweet spots appear bifurcated: be smaller than 600 or bigger than 800.

Nevertheless, a firm’s ability to grow RPL is a far stronger indicator of long-term financial success. As a group, the Premier League firms average $1.8 million in RPL—more than double the RPL of $867,000 for 45 firms in the Everyone Else category. RPL is a factor of four variables: productivity, rate levels, timekeeper mix and cash realization. While imperfect, it remains the best available proxy measure of a firm’s current market position because it captures pricing power, access to premium mandates and ability to match supply to demand. Over time, sustained RPL gains are highly suggestive of upmarket advancement.

Place Isn’t a Strategy

The astounding success of Kirkland and Latham raises questions worth exploring. Are we living in the age of the megafirm? Is the hegemony of the New York elite on the decline? What makes a firm national or global—and is that a question of physical presence or a more abstract notion of brand in the minds of clients and talent?

Based on NLJ 500 office data from 2021, this graphic sorts the 45 Premier and Championship League firms into five categories. This footprint analysis helps us tease out a few key insights on how Big Law’s winningest firms think about geography.

It’s worth noting that none of the 45 firms in our power rankings competes in more than 10 states—suggesting that winning firms are intentional in choosing where to play.

On the global stage, we can trace three distinct pathways for New York’s old-line elite. A handful have stuck to what they know and remained home, and the numbers show this is a viable strategy. Capital markets firms generally compete with 70% or more of their head count in global financial centers across three to seven countries, with 50% to 70% remaining in the Big Apple. Most are in the 700- to 1,000-lawyer range. Globalists cover more ground, competing in 12 or more countries; these are the firms that are taking the creamiest mandates away from the much-beleaguered global platform category, but the sustained outperformance by White & Case demonstrates that success is possible even amid currency fluctuations and geopolitical unrest around the world.

The 21 ranked international firms display a greater diversity of footprint choices, competing in five to 11 countries with at least 70% of head count remaining in the U.S. All of these firms have now invaded the New York market, with 12% to 50% of their U.S. lawyers in the Big Apple and 30% to 70% of head count in major U.S. markets. Silicon Valley is emerging as a critical battleground as Fenwick & West, Cooley and Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati continue to shoot the lights out, particularly as the U.K.-born global firms eye another round of U.S. market entry with their sights set on the emerging companies and venture capital firms that fund the feeding and care of would-be unicorns.

A closer look at the Championship League and the firms that just missed the cut gives a few clues as to what’s coming for the Am Law 200 in 2022 and beyond: a strategic sorting and the emergence of “super regions” as erstwhile “King of the Hill” firms advance to play for a bigger pie on a bigger stage.

Since the Great Recession, Atlanta powerhouse King & Spalding has won resoundingly in the Southeast—and taken a bite out of the energy business of the old-line Texas firms. (Holland & Knight follows this path into Texas via last year’s tie-up with Thompson & Knight.) In 2022, it competes internationally, with about 15% of head count outside the U.S. Its geographic footprint is designed to fit its key practices and sectors. Alston & Bird is now the likely reigning champ in the Southeast, but expect added competition as Troutman Pepper Hamilton Sanders completes operational and commercial integration up and down the I-95 corridor, bookended by its Philadelphia stronghold and longstanding Atlanta client base.

Similarly, Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld has long since expanded out of its Texas roots to the D.C. market, where bench depth in regulatory expertise burnished its reputation to contend credibly among the national elite. Akin’s lackluster financial results during the pandemic raise questions about its practice mix and suggest that expansion into top-tier legal markets like New York and London is not without risk. Meanwhile, Vinson & Elkins has stayed closer to home, with over half of its lawyers still in Texas, posting reliable and steady, if modest, gains in RPL and partner compensation in most years.

Practice, Sector and Geography

Since its inception and for most of its history, the modern law firm has been bound by locality and defined by a sense of physical place. Jurisdictional borders gave rise to the development of many micro-markets for legal services, while the law office has shaped the lived experiences—and resulting cultural character—of Big Law.

Waves of expansion and consolidation, riding on macroeconomic shifts toward globalization, have now blurred the once-clear demarcation of local markets. In tandem with these shifts, most firms have moved away from geography-centered organization to practice-oriented management and leadership.

Now, many managing partners and chief marketing officers of law firms are pushing another pivot toward sector orientation. Too often, these debates are focused internally on questions of influence and control over questions of how the firm will allocate finite resources. This hurts firms twice: first by drawing partner attention inward rather than toward clients and competitors, and second by seriously mischaracterizing how practice, sector and geography actually intersect to comprise strategic decision-making.

By and large, practice orientation makes intuitive sense to lawyers. The preeminent firms that sit atop the Big Law pecking order have always been practice-led. The triple halos of reputation, prestige and profitability all emanate from feats of elite lawyering. Marty Lipton’s poison pill is the best-known example of legal innovation, but most law firm origin stories are built on groundbreaking legal expertise applied to high-stakes commercial problems, whether in the boardroom or the courtroom.

What is less obvious and less well known is that preeminent firms achieved their standing via sector focus. The most enduring and illustrious shingles still standing in the American legal market came to rise at the turn of the century and the peak of the second Industrial Revolution. The very first key sectors in Big Law were railroads, utilities and steel—and the banks that financed the epic challenge of capitalizing commercial ventures of a size and scale never before seen in history.

Seventy years before Wachtell came to dominate the M&A scene by defending companies from the wave of hostile takeovers financed by corporate raiders, Frank Stetson invented the corporate trust indenture, the legal device that enabled the efficient aggregation of enormous levels of capital and imposed order on creditor disputes in the days before the federal bankruptcy code existed. Stetson would go on to become known as J.P. Morgan’s “attorney general” and his firm the counsel of choice for the mighty Morgan bank for decades to come. That firm still stands today atop most league tables, including our own, under the shingle of Davis Polk & Wardwell. In 1896, Paul Cravath cemented his legendary reputation—at the age of 36—by brokering peace in the epic 12-year legal battle between Edison and Westinghouse for control of electric power by means of a shared hegemony over patents and pricing.

These are the origin stories of Wachtell, Davis Polk and Cravath. More importantly, they are also the origin stories of antitrust, capital markets, corporate finance and restructuring—still among the toniest practices in Big Law.

These origin stories are often repeated, but the ensuing takeaways are often misleading. The towering talents of legendary lawyers like Lipton, Stetson and Cravath are undeniable, but the conditions that led to their legal innovations provide worthier and more fruitful lines of inquiry. Tremendous feats of lawyering happen at points of great pressure and friction, at the intersection of legal expertise and client need. Lipton, Stetson and Cravath all toiled for decades at intractable legal problems that occurred because the commercial requirements of their clients strained existing statutory and regulatory frameworks. The insights underlying their legal victories were only possible because they engaged deeply with the market realities confronting the banks, the railroads and the utilities.

In 2022, many top-flight deal lawyers and litigators still consider themselves sector-agnostic, and law firm management committees remain mired in internal strife as practice, sector and office leaders vie for influence. Such debates miss the point entirely, because practices, sectors and geographies all have a distinct role to play in law firm competitive strategy. All three must work in concert to propel the firm forward.

Winning at the Intersection

When it comes to the relationship between practice, sector and geography, sector teams are the scouts: They scan the horizon and explore the terrain for emerging issues and new opportunities. In essence, sector orientation is market orientation. In a business environment that is only getting more complex, the defining traits of first-rate legal counsel are foresight and commerciality—long desired by clients and elusive for most law firms.

For the firms that can develop true sector focus and depth, the rewards can be great. Over 75% of the firms that made our league tables invest in sector-driven strategies. When done right, sector-led planning ensures that the firm pursues go-to-market pathways that are demand-led and client-focused. The prize for lawyers is expanded opportunity to tackle meaningful, high-stakes mandates. For equity partners, sector orientation promises a more consistent ability to generate demand and revenue at top-of-market rates.

Practice teams work and win together to solve client problems, and so practice groups nurture the bonds of friendship and collegiality that most lawyers prize and seek in the workplace. From a strategic standpoint, practices are the wellspring of a firm’s competitive advantage because expertise and know-how coalesce around legal issues. Subsequently, the training and development of young lawyers must remain the brief of practice leadership.

Geographies have waned in importance at many leading firms simply because there are no more lands to conquer. Decades of consolidation and the rise of a perpetually frothy lateral market have left every major legal market a bloody red ocean of intense competition. Especially in the post-pandemic age, the office remains a critical anchor in law firm strategy and operations because this is where law firms make—and deliver on—the talent-facing brand promise. Other minds will debate the merits of virtual and hybrid working arrangements and what the optimal future of work looks like. For the foreseeable future, offices remain the keepers of the employee experience and the operational sausage-making that keeps the trainings running on time.

Perennially successful firms know the perils of copycat strategy, and the top performers are those that compete with a clear-eyed view of their current position. The winningest firms in Big Law know that markets aren’t simply physical places anymore. Today, legal markets form at the intersection of practice, sector and geography—and winning firms win by pulling together a fluid combination of practice expertise in the right collection of locations to meet the needs of specific clients.

Jae Um is founder and executive director of Six Parsecs.

METHODOLOGY

League tables are set based on a composite score of 2021 PPEP, CAP and head count growth in 2020 and 2021. The rankings within Premier and Championship Leagues are based on a weighted composite score of current RPL, PEP and CAP, as well as short-term, mid-term and long-term gains on RPL and CAP on an inflation-adjusted basis. Weighting is applied to emphasize recent gains. “Practice Cachet” and “Sector Focus” ratings are based on an analysis of the Chambers USA Nationwide Guide for 2021; 45 ranked firms combined for just under 1,000 appearances on 123 tables, with about half the tables indicating some sector orientation. Weighting was applied for higher band rankings and two separate scores calculated after normalizing for size.

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

Paul Hastttings ranking destroys any semblance of credibility. Likewise the spurn of GDC. At neither btwAnonymous User wrote: ↑Tue Apr 26, 2022 8:20 pm

Premier League Table

1. Watchtell

2. Davis Polk

3. Simpson Thacher

4. Kirkland

5. Sullivan & Cromwell

6. Latham

7. Debevoise

8. Paul Weiss

9. Cahill

10. Ropes & Gray

11. Paul Hastings

12. Milbank

13. Weil

14. Cravath

15. Fenwick

16. Skadden

17. Fried Frank

18. Quinn Emmanuel

19. Gibson Dunn

20. Cleary

NP. Cooley

NP. Goodwin

Championship League

23. Sidley Austin

24. Willkie Farr

25. King & Spalding

26. Proskauer Rose

27. Dechert

28. McDermott

29. Wilson Sonsini

30. Cadwalader

31. Vinson & Elkins

32. White & Case

33. Wilmer

34. Schulte

35. Alston & Bird

36. Akin Gump

37. Winston & Strawn

38. Orrick

39. Kramer Levin

40. Covington

41. O'Melveny

42. Sheppard Mullin

43. Morgan Lewis

44. Pillsbury

45. Shearman

Full Article:

Kings of the Hill: Power Ranking the Am Law 100 Based on Momentum, Profit and Prestige

As firms fight for Big Law standing, a segmentation analysis of the Am Law 100 reveals shifts in the pecking order.

By Jae Um

For most casual observers, Kirkland & Ellis and Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz represent the pinnacle of success in Big Law. Kirkland capped off a fairytale decade with $6.04 billion in revenue in 2021 and $7.4 million in profits per equity partner. Wachtell retained pole position—for the 15th year in a row—in per-lawyer metrics with $3.9 million in revenue per lawyer and $8.4 million in PEP.

But the two firms take starkly different routes to prestige and profit. Kirkland is a powerhouse megafirm with head count exceeding 3,000, a two-tier partnership and the most aggressive growth strategy in the business. Wachtell has remained small and mighty, with fewer than 300 lawyers in a single office in New York, zero nonequity partners, and a lockstep compensation system.

Since its inception, the Am Law 100 has never been a homogenous group. A prevailing philosophy of manifest destiny has led many firms to expand and consolidate, creating a cadre of self-described full-service national firms. Most firms rule the roost in their own backyards, but an increasing number are expanding aggressively for international reach. Specialists like Littler Mendelson and Fish & Richardson are listed alongside global platforms like Baker McKenzie and DLA Piper.

Are these firms really in the same business? What do these diversifying strategies tell us about the direction of travel and varying pathways to success in today’s legal market?

Power Rankings: Momentum, Profit and Prestige

To help make sense of an increasingly frenetic and complex legal market, Six Parsecs constructed a scoring model for the 2022 Am Law 100. The methodology is designed to measure momentum as well as profit and prestige, with emphasis on profitable growth and upward trajectory in key metrics.

Modeled after the English Premier League, these power rankings define two divisions. The core model places 20 firms in the Premier League, giving us a roster of highly recognizable global elites alongside a few surprising names that underline the emerging influence of private capital as well as the dominance of technology and life sciences at the world’s most prestigious firms.

The next tier of firms—what we’ll call the Championship League—includes those currently winning in their regions and categories. Like the EPL, the model flags promotion and relegation candidates to better reflect the fluidity of legal business and volatility we’ve observed in legal markets in the past decade—reminding firms that position is not destiny, neither success nor failure is eternal, and we always live to fight another day.

The intent of this study is to reflect the zeitgeist of the industry in a watershed year. These league tables highlight the firms that are competing most fiercely to move upmarket in an increasingly volatile environment.

Which firms are on the rise? Who’s winning the battle for talent? Is all growth good? What commonalities do successful firms share? Which strategies and tactics are unique to a certain cohort of firms and which are universally applicable?

These are the questions that are often top of mind for law firm leaders. To place greater context around these power rankings, we’ve also integrated analysis of footprint, practice mix and sector focus. Based on this analysis, we delve into the strategy playbooks defining competition today.

Bigger Isn’t Better

The ascendancy of Kirkland and Latham & Watkins has fueled a common narrative that getting bigger is a positive. The sequel narratives that follow are troubling: growth is necessary and growth equals success.

Get More Information Get More Information

A quantitative analysis of the Am Law 100 over the last 10 years indicates little to no correlation between size and financial performance. An analysis of 45 firms that comprise “Everyone Else” in these rankings shows that firms with fewer than 500 lawyers outperformed larger firms on both RPL and average partner compensation. On balance, larger firms are harder to manage, and the data suggests that indiscriminate pursuit of head count growth is a risk indicator. The largest firms by head count are often firms with a global footprint in emerging markets with challenging price pressures.

Size is not what sets Kirkland and Latham apart from the pack. Foresight, boldness and focus are far more controlling attributes that have allowed these two firms to establish and hold dominant positions. The reshaping of global capital markets away from public markets to private equity and the increasing sophistication and specialization of debt instruments created huge opportunities for law firms. Despite—or, perhaps, because of—the length and depth of relationships between the bankers and lawyers of Wall Street, Kirkland and Latham got the jump on private equity giants Blackstone, KKR, TPG and the Carlyle Group.

On a five-year basis, the Am Law 100 firms with most aggressive head count growth comprise a mixed bag. A few rising stars like Goodwin Procter and Cooley have managed to grow while moving upmarket and improving profitability. Down-market players like Lewis Brisbois Bisgaard & Smith and Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani have both grown head count by over 40% with uneven results on partner compensation, with RPL hovering around the $450,000 to $500,000 range and CAP in the $350,000 to $425,000 range.

At the other end of the spectrum, longstanding powerhouse Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom has contracted head count by 10% in the last decade while posting consistently strong performance in profitability. In fact, Skadden is the only firm that has managed to post consistent gains in partner compensation that beat inflation every single year since the Great Recession. Sullivan & Cromwell and Cravath, Swaine & Moore have both maintained essentially the same head count over the past five years while achieving outstanding gains in RPL and PEP.

It is true that certain size thresholds offer advantages to help diversify practice mix and to establish sufficient operating scale to make critical infrastructure investments. Up and down our league tables, the sweet spots appear bifurcated: be smaller than 600 or bigger than 800.

Nevertheless, a firm’s ability to grow RPL is a far stronger indicator of long-term financial success. As a group, the Premier League firms average $1.8 million in RPL—more than double the RPL of $867,000 for 45 firms in the Everyone Else category. RPL is a factor of four variables: productivity, rate levels, timekeeper mix and cash realization. While imperfect, it remains the best available proxy measure of a firm’s current market position because it captures pricing power, access to premium mandates and ability to match supply to demand. Over time, sustained RPL gains are highly suggestive of upmarket advancement.

Place Isn’t a Strategy

The astounding success of Kirkland and Latham raises questions worth exploring. Are we living in the age of the megafirm? Is the hegemony of the New York elite on the decline? What makes a firm national or global—and is that a question of physical presence or a more abstract notion of brand in the minds of clients and talent?

Based on NLJ 500 office data from 2021, this graphic sorts the 45 Premier and Championship League firms into five categories. This footprint analysis helps us tease out a few key insights on how Big Law’s winningest firms think about geography.

It’s worth noting that none of the 45 firms in our power rankings competes in more than 10 states—suggesting that winning firms are intentional in choosing where to play.

On the global stage, we can trace three distinct pathways for New York’s old-line elite. A handful have stuck to what they know and remained home, and the numbers show this is a viable strategy. Capital markets firms generally compete with 70% or more of their head count in global financial centers across three to seven countries, with 50% to 70% remaining in the Big Apple. Most are in the 700- to 1,000-lawyer range. Globalists cover more ground, competing in 12 or more countries; these are the firms that are taking the creamiest mandates away from the much-beleaguered global platform category, but the sustained outperformance by White & Case demonstrates that success is possible even amid currency fluctuations and geopolitical unrest around the world.

The 21 ranked international firms display a greater diversity of footprint choices, competing in five to 11 countries with at least 70% of head count remaining in the U.S. All of these firms have now invaded the New York market, with 12% to 50% of their U.S. lawyers in the Big Apple and 30% to 70% of head count in major U.S. markets. Silicon Valley is emerging as a critical battleground as Fenwick & West, Cooley and Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati continue to shoot the lights out, particularly as the U.K.-born global firms eye another round of U.S. market entry with their sights set on the emerging companies and venture capital firms that fund the feeding and care of would-be unicorns.

A closer look at the Championship League and the firms that just missed the cut gives a few clues as to what’s coming for the Am Law 200 in 2022 and beyond: a strategic sorting and the emergence of “super regions” as erstwhile “King of the Hill” firms advance to play for a bigger pie on a bigger stage.

Since the Great Recession, Atlanta powerhouse King & Spalding has won resoundingly in the Southeast—and taken a bite out of the energy business of the old-line Texas firms. (Holland & Knight follows this path into Texas via last year’s tie-up with Thompson & Knight.) In 2022, it competes internationally, with about 15% of head count outside the U.S. Its geographic footprint is designed to fit its key practices and sectors. Alston & Bird is now the likely reigning champ in the Southeast, but expect added competition as Troutman Pepper Hamilton Sanders completes operational and commercial integration up and down the I-95 corridor, bookended by its Philadelphia stronghold and longstanding Atlanta client base.

Similarly, Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld has long since expanded out of its Texas roots to the D.C. market, where bench depth in regulatory expertise burnished its reputation to contend credibly among the national elite. Akin’s lackluster financial results during the pandemic raise questions about its practice mix and suggest that expansion into top-tier legal markets like New York and London is not without risk. Meanwhile, Vinson & Elkins has stayed closer to home, with over half of its lawyers still in Texas, posting reliable and steady, if modest, gains in RPL and partner compensation in most years.

Practice, Sector and Geography

Since its inception and for most of its history, the modern law firm has been bound by locality and defined by a sense of physical place. Jurisdictional borders gave rise to the development of many micro-markets for legal services, while the law office has shaped the lived experiences—and resulting cultural character—of Big Law.

Waves of expansion and consolidation, riding on macroeconomic shifts toward globalization, have now blurred the once-clear demarcation of local markets. In tandem with these shifts, most firms have moved away from geography-centered organization to practice-oriented management and leadership.

Now, many managing partners and chief marketing officers of law firms are pushing another pivot toward sector orientation. Too often, these debates are focused internally on questions of influence and control over questions of how the firm will allocate finite resources. This hurts firms twice: first by drawing partner attention inward rather than toward clients and competitors, and second by seriously mischaracterizing how practice, sector and geography actually intersect to comprise strategic decision-making.

By and large, practice orientation makes intuitive sense to lawyers. The preeminent firms that sit atop the Big Law pecking order have always been practice-led. The triple halos of reputation, prestige and profitability all emanate from feats of elite lawyering. Marty Lipton’s poison pill is the best-known example of legal innovation, but most law firm origin stories are built on groundbreaking legal expertise applied to high-stakes commercial problems, whether in the boardroom or the courtroom.

What is less obvious and less well known is that preeminent firms achieved their standing via sector focus. The most enduring and illustrious shingles still standing in the American legal market came to rise at the turn of the century and the peak of the second Industrial Revolution. The very first key sectors in Big Law were railroads, utilities and steel—and the banks that financed the epic challenge of capitalizing commercial ventures of a size and scale never before seen in history.

Seventy years before Wachtell came to dominate the M&A scene by defending companies from the wave of hostile takeovers financed by corporate raiders, Frank Stetson invented the corporate trust indenture, the legal device that enabled the efficient aggregation of enormous levels of capital and imposed order on creditor disputes in the days before the federal bankruptcy code existed. Stetson would go on to become known as J.P. Morgan’s “attorney general” and his firm the counsel of choice for the mighty Morgan bank for decades to come. That firm still stands today atop most league tables, including our own, under the shingle of Davis Polk & Wardwell. In 1896, Paul Cravath cemented his legendary reputation—at the age of 36—by brokering peace in the epic 12-year legal battle between Edison and Westinghouse for control of electric power by means of a shared hegemony over patents and pricing.

These are the origin stories of Wachtell, Davis Polk and Cravath. More importantly, they are also the origin stories of antitrust, capital markets, corporate finance and restructuring—still among the toniest practices in Big Law.

These origin stories are often repeated, but the ensuing takeaways are often misleading. The towering talents of legendary lawyers like Lipton, Stetson and Cravath are undeniable, but the conditions that led to their legal innovations provide worthier and more fruitful lines of inquiry. Tremendous feats of lawyering happen at points of great pressure and friction, at the intersection of legal expertise and client need. Lipton, Stetson and Cravath all toiled for decades at intractable legal problems that occurred because the commercial requirements of their clients strained existing statutory and regulatory frameworks. The insights underlying their legal victories were only possible because they engaged deeply with the market realities confronting the banks, the railroads and the utilities.

In 2022, many top-flight deal lawyers and litigators still consider themselves sector-agnostic, and law firm management committees remain mired in internal strife as practice, sector and office leaders vie for influence. Such debates miss the point entirely, because practices, sectors and geographies all have a distinct role to play in law firm competitive strategy. All three must work in concert to propel the firm forward.

Winning at the Intersection

When it comes to the relationship between practice, sector and geography, sector teams are the scouts: They scan the horizon and explore the terrain for emerging issues and new opportunities. In essence, sector orientation is market orientation. In a business environment that is only getting more complex, the defining traits of first-rate legal counsel are foresight and commerciality—long desired by clients and elusive for most law firms.

For the firms that can develop true sector focus and depth, the rewards can be great. Over 75% of the firms that made our league tables invest in sector-driven strategies. When done right, sector-led planning ensures that the firm pursues go-to-market pathways that are demand-led and client-focused. The prize for lawyers is expanded opportunity to tackle meaningful, high-stakes mandates. For equity partners, sector orientation promises a more consistent ability to generate demand and revenue at top-of-market rates.

Practice teams work and win together to solve client problems, and so practice groups nurture the bonds of friendship and collegiality that most lawyers prize and seek in the workplace. From a strategic standpoint, practices are the wellspring of a firm’s competitive advantage because expertise and know-how coalesce around legal issues. Subsequently, the training and development of young lawyers must remain the brief of practice leadership.

Geographies have waned in importance at many leading firms simply because there are no more lands to conquer. Decades of consolidation and the rise of a perpetually frothy lateral market have left every major legal market a bloody red ocean of intense competition. Especially in the post-pandemic age, the office remains a critical anchor in law firm strategy and operations because this is where law firms make—and deliver on—the talent-facing brand promise. Other minds will debate the merits of virtual and hybrid working arrangements and what the optimal future of work looks like. For the foreseeable future, offices remain the keepers of the employee experience and the operational sausage-making that keeps the trainings running on time.

Perennially successful firms know the perils of copycat strategy, and the top performers are those that compete with a clear-eyed view of their current position. The winningest firms in Big Law know that markets aren’t simply physical places anymore. Today, legal markets form at the intersection of practice, sector and geography—and winning firms win by pulling together a fluid combination of practice expertise in the right collection of locations to meet the needs of specific clients.

Jae Um is founder and executive director of Six Parsecs.

METHODOLOGY

League tables are set based on a composite score of 2021 PPEP, CAP and head count growth in 2020 and 2021. The rankings within Premier and Championship Leagues are based on a weighted composite score of current RPL, PEP and CAP, as well as short-term, mid-term and long-term gains on RPL and CAP on an inflation-adjusted basis. Weighting is applied to emphasize recent gains. “Practice Cachet” and “Sector Focus” ratings are based on an analysis of the Chambers USA Nationwide Guide for 2021; 45 ranked firms combined for just under 1,000 appearances on 123 tables, with about half the tables indicating some sector orientation. Weighting was applied for higher band rankings and two separate scores calculated after normalizing for size.

Edit: and lol at skadden on verge of relegation

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

Which is deemed to be more credible and widely referred to? The vault rankings or Am100? Does anyone also know what the different ranking methodologies are?

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

Chambers band rankings for practice groups.Anonymous User wrote: ↑Wed Apr 27, 2022 1:26 amWhich is deemed to be more credible and widely referred to? The vault rankings or Am100? Does anyone also know what the different ranking methodologies are?

-

Sackboy

- Posts: 1045

- Joined: Fri Mar 27, 2020 2:14 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

Vault tracks traditional prestige from the eyes of law students and a fair number of practitioners, primarily for NY but its rankings affect how firms are viewed in all markets by some lawyers.Anonymous User wrote: ↑Wed Apr 27, 2022 1:36 amChambers band rankings for practice groups.Anonymous User wrote: ↑Wed Apr 27, 2022 1:26 amWhich is deemed to be more credible and widely referred to? The vault rankings or Am100? Does anyone also know what the different ranking methodologies are?

Chambers tracks the actual quality of practice groups in terms of both workflow and lawyers.

AmLaw tracks nothing but size and, imo, is the most useless metric.

Register now!

Resources to assist law school applicants, students & graduates.

It's still FREE!

Already a member? Login

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

Enter their new King of the Hill/Premier & Champions League Tables, which seems to be a composite of RPL, PEP, and Chambers rankings...at least it has WLRK at top post, already gets more validity from me than Vault for that.

I'm sure they'll enjoy the heightened readership, who isn't a simp for rankings anyway /s

-

Sackboy

- Posts: 1045

- Joined: Fri Mar 27, 2020 2:14 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

I don't think any of those are going to reasonably catch on. The thing about rankings is they need to be super simple to the point where you can boil it down to AmLaw 50, Chambers Band 2, V20, etc.Anonymous User wrote: ↑Wed Apr 27, 2022 2:33 amEnter their new King of the Hill/Premier & Champions League Tables, which seems to be a composite of RPL, PEP, and Chambers rankings...at least it has WLRK at top post, already gets more validity from me than Vault for that.

I'm sure they'll enjoy the heightened readership, who isn't a simp for rankings anyway /s

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

AmLaw tracks profitability as well. Aside from the premier league and all that crap, AmLaw does what it purports do - comparing actual law firm performance by numbersSackboy wrote: ↑Wed Apr 27, 2022 1:51 amVault tracks traditional prestige from the eyes of law students and a fair number of practitioners, primarily for NY but its rankings affect how firms are viewed in all markets by some lawyers.Anonymous User wrote: ↑Wed Apr 27, 2022 1:36 amChambers band rankings for practice groups.Anonymous User wrote: ↑Wed Apr 27, 2022 1:26 amWhich is deemed to be more credible and widely referred to? The vault rankings or Am100? Does anyone also know what the different ranking methodologies are?

Chambers tracks the actual quality of practice groups in terms of both workflow and lawyers.

AmLaw tracks nothing but size and, imo, is the most useless metric.

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

Do we know how accurate AmLaw numbers are, though? I wonder if firms basically self-report (i.e. just plug numbers of their choosing into a questionnaire); or whether they are forced to provide audited financial statements & other documentation. Obviously the latter would be a lot more credible than the former.Anonymous User wrote: ↑Wed Apr 27, 2022 6:42 amAmLaw tracks profitability as well. Aside from the premier league and all that crap, AmLaw does what it purports do - comparing actual law firm performance by numbers

The AmLaw methodology section says the following:

…this doesn’t exactly inspire confidence either. Since I don’t think AmLaw ever reveals which firms are ‘real’ data and which firms’ numbers are “estimates based on our reporting.” (For the firms, the incentives are asymmetric, since if AmLaw “estimates” your numbers too low, you can correct them; if they over-estimate your metrics, then the firm would stay silent.) Nor do we know the ratio of the two — what if something crazy like half of the AmLaw 100 are made-up estimates?Most law firms provide their financials voluntarily for this report. Some choose not to cooperate, so we make estimates based on our reporting. But all data is investigated by our reporters.

Get unlimited access to all forums and topics

Register now!

I'm pretty sure I told you it's FREE...

Already a member? Login

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

My old firm used to present our profitability numbers to us annually which more or less matched AmLaw numbers. Of course, the firm could be cooking the books generally and present inflated numbers to associates and AmLaw. But, we were given a bit more detail on how those numbers worked out (ie average hours worked, collection rates, average pay for counsel and income partners etc.)Anonymous User wrote: ↑Wed Apr 27, 2022 6:55 amDo we know how accurate AmLaw numbers are, though? I wonder if firms basically self-report (i.e. just plug numbers of their choosing into a questionnaire); or whether they are forced to provide audited financial statements & other documentation. Obviously the latter would be a lot more credible than the former.Anonymous User wrote: ↑Wed Apr 27, 2022 6:42 amAmLaw tracks profitability as well. Aside from the premier league and all that crap, AmLaw does what it purports do - comparing actual law firm performance by numbers

The AmLaw methodology section says the following:…this doesn’t exactly inspire confidence either. Since I don’t think AmLaw ever reveals which firms are ‘real’ data and which firms’ numbers are “estimates based on our reporting.” (For the firms, the incentives are asymmetric, since if AmLaw “estimates” your numbers too low, you can correct them; if they over-estimate your metrics, then the firm would stay silent.) Nor do we know the ratio of the two — what if something crazy like half of the AmLaw 100 are made-up estimates?Most law firms provide their financials voluntarily for this report. Some choose not to cooperate, so we make estimates based on our reporting. But all data is investigated by our reporters.

Unless firms are allowed to go public, we'll never really know. AmLaw just happens to be our best guess.

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

One reason to trust the AmLaw numbers is that multiple people inside of a firm likely have access to the financials and presumably would not feel comfortable if they saw a significant deviation from the actual numbers. This compares favorably with law school metrics submitted to USNWR, which are often known and submitted only by one person.Anonymous User wrote: ↑Wed Apr 27, 2022 6:55 amDo we know how accurate AmLaw numbers are, though? I wonder if firms basically self-report (i.e. just plug numbers of their choosing into a questionnaire); or whether they are forced to provide audited financial statements & other documentation. Obviously the latter would be a lot more credible than the former.Anonymous User wrote: ↑Wed Apr 27, 2022 6:42 amAmLaw tracks profitability as well. Aside from the premier league and all that crap, AmLaw does what it purports do - comparing actual law firm performance by numbers

The AmLaw methodology section says the following:…this doesn’t exactly inspire confidence either. Since I don’t think AmLaw ever reveals which firms are ‘real’ data and which firms’ numbers are “estimates based on our reporting.” (For the firms, the incentives are asymmetric, since if AmLaw “estimates” your numbers too low, you can correct them; if they over-estimate your metrics, then the firm would stay silent.) Nor do we know the ratio of the two — what if something crazy like half of the AmLaw 100 are made-up estimates?Most law firms provide their financials voluntarily for this report. Some choose not to cooperate, so we make estimates based on our reporting. But all data is investigated by our reporters.

-

Sackboy

- Posts: 1045

- Joined: Fri Mar 27, 2020 2:14 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

I think my main point is that as a "ranking" AmLaw, which was the original question, when referenced by lawyers, is a reflection of revenue. It's wonderful that it tracks other stuff, but knowing that a firm is AmLaw 10 vs 30 doesn't mean terribly much. You'd have to dig into each individual data point to get any real value out of AmLaw, which is pretty bad for a ranking when you need to dive into individual components of its methodology.

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

Is the RPL spread usually that tightAnonymous User wrote: ↑Tue Apr 26, 2022 8:02 pmPPEPAnonymous User wrote: ↑Tue Apr 26, 2022 6:27 pmCan someone post a top 10 on each of the metrics (or at least a couple). I could only find gross rev on ATL

Wachtell $8,400,000

Kirkland $7,388,000

DPW $7,010,000

S&C $6,366,000

P, W $6,162,000

STB $5,980,000

Cravath $5,803,000

Quinn $5,746,000

Latham $5,705,000

Cahill $5,533,000

Rest are: Weil, Skadden, Milbank, Deb (all 5 million plus). Paul Hastings, Cleary, Gibson, Cadwalader, K&S, Ropes, Fried Frank, Dechert, Cooley: all 4 million plus.

RPL

Wachtell 3,860,000

S&C 2,215,000

Cravath 2,035,000

Kirkland 1,997,000

Ropes & Gray 1,950,00

DPW 1,923,00

STB 1,913,000

Quinn 1,839,000

Skadden 1,838,00

P, W 1,836,000

10-25 is: Cahill, Latham, Fenwick, Deb, Milbank, Proskauer, Fried Frank, Gibson Dunn, Paul Hastings, Weil, Cooley, Wilmer, Goodwin, Sidley, Cadawalader (Cahill at 1,818,000 and Cadwalader at 1,474,00)

Revenue

Revenue is kinda dumb so just giving: Kirkland (6 billion), Latham (5 billion), DLA, Baker, Skadden (3 billion).

Communicate now with those who not only know what a legal education is, but can offer you worthy advice and commentary as you complete the three most educational, yet challenging years of your law related post graduate life.

Register now, it's still FREE!

Already a member? Login

-

Sackboy

- Posts: 1045

- Joined: Fri Mar 27, 2020 2:14 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

Yep. WLRK is always 1.5x-2.0x the 2nd place, and then there is always a tight grouping for the next ~5-10 spots.

-

Anonymous User

- Posts: 432857

- Joined: Tue Aug 11, 2009 9:32 am

Re: Am Law 100 2022

Yes - outside of Wachtell, the big difference in revenue and PPP is made via levarage+size. The top firms associates are all billed out at similar rates and work similar hours, so I wouldn't expect RPL to have a huge variance.Anonymous User wrote: ↑Wed Apr 27, 2022 11:55 amIs the RPL spread usually that tightAnonymous User wrote: ↑Tue Apr 26, 2022 8:02 pmPPEPAnonymous User wrote: ↑Tue Apr 26, 2022 6:27 pmCan someone post a top 10 on each of the metrics (or at least a couple). I could only find gross rev on ATL

Wachtell $8,400,000

Kirkland $7,388,000

DPW $7,010,000

S&C $6,366,000

P, W $6,162,000

STB $5,980,000

Cravath $5,803,000

Quinn $5,746,000

Latham $5,705,000

Cahill $5,533,000

Rest are: Weil, Skadden, Milbank, Deb (all 5 million plus). Paul Hastings, Cleary, Gibson, Cadwalader, K&S, Ropes, Fried Frank, Dechert, Cooley: all 4 million plus.

RPL

Wachtell 3,860,000

S&C 2,215,000

Cravath 2,035,000

Kirkland 1,997,000

Ropes & Gray 1,950,00

DPW 1,923,00

STB 1,913,000

Quinn 1,839,000

Skadden 1,838,00

P, W 1,836,000

10-25 is: Cahill, Latham, Fenwick, Deb, Milbank, Proskauer, Fried Frank, Gibson Dunn, Paul Hastings, Weil, Cooley, Wilmer, Goodwin, Sidley, Cadawalader (Cahill at 1,818,000 and Cadwalader at 1,474,00)

Revenue

Revenue is kinda dumb so just giving: Kirkland (6 billion), Latham (5 billion), DLA, Baker, Skadden (3 billion).

-

Moneytrees

- Posts: 934

- Joined: Tue Jan 14, 2014 11:41 pm

Re: Am Law 100 2022

The "premier league" and "championship league" table is bizarre and confusing.

-

Buglaw

- Posts: 195

- Joined: Wed Dec 25, 2019 9:24 pm

Re: Am Law 100 2022

The whole list makes no sense. In what world is Fenwick and Paul Hastings ahead of Cooley? Why are firms like Sheppard Mullin and Dechert on the list, but not Mayer Brown. Why is Sidley so low? Why Is Kirland international and Latham Globalist? How is Cahill ahead of Cravath?Moneytrees wrote: ↑Wed Apr 27, 2022 5:27 pmThe "premier league" and "championship league" table is bizarre and confusing.

This is the dumbest list on the planet and WAYYYYYYY worse than Vault. IDK why they thought this was a good idea.

Seriously? What are you waiting for?

Now there's a charge.

Just kidding ... it's still FREE!

Already a member? Login