This is from PMs I sent someone else about RC passages:

vanwinkle wrote:The effective strategy for RC is to do the easiest passage first. The reason for this is that it takes less time to answer an easy question, and you're more likely to get an easy question right if you spend time on it, so doing it from easiest->hardest is the most time efficient. You only have 35 minutes, so increasing the speed at which you answer can lead to more correct answers. Not only that, but if you get stuck answering hard questions first, you'll start to feel frustrated easily, while doing easy questions first can help you feel calm and like you know what you're doing as you build up toward the harder ones.

Though it sounds counterintuitive, you have to "waste" the first 60 seconds of your RC section ranking the passages in order of difficulty. Some simple ways to rank them:

1) Very quickly read the first two sentences of each passage, just to see how long the sentences are and how many big words they use. This is useful because a passage is nearly always consistent in its density; if the first paragraph is easy to read, the second and third and fourth should be just as easy, and vice versa. The easiest passage should be the one with short sentences and fairly simple words that's easy to understand.

2) Look at the length of the questions and answers. If all the questions in a section are 1-2 lines long and the answers are all a few words each, those are going to be fairly simple to figure out how to answer. The hardest section will have questions that are 3-4 lines long, and some answers that are also 3-4 lines long.

3) Look for questions that refer to specific lines. For instance, if there are three questions in a section that say "On line 27 the author states," "What does ____ on line 33 mean?" and "What does the last paragraph stand for?" then those questions will be very easy to answer because they're already telling you where to look in the passage for the answer! That section is probably worth doing first or second.

4) The science section is often the hardest. If you look at the science section and you go "Bwuh?", and it even comes close to being the hardest under the guidelines above, then do it last. It's rare for the science topic to be the easiest or even the second-easiest.

Rank them 1-4 from easiest to hardest. If you practice you can do this within 60 seconds. Then do the easiest one first. Read the passage, and then go not to the first question, but what looks like the easiest question for that passage! Within each RC passage, do the questions from easiest to hardest (for example, ones that point you to a specific line in the passage will be easier because they tell you where to look for the answer). While you're doing the easy ones you'll continue to reread and soak in the passage, so you'll understand it better by the time you get to the hard ones. That way you're absorbing the passage as you answer the questions and work your way up to the difficult questions that require a better understanding of everything. Don't waste your time writing down anything unless you have to.

Plan on not coming back to a section when you finish, since you're likely to run out of time; if you get stumped and feel like you'll have to spend too much time on a particular question, guess and move on.

Last point: If you're going to guess, ALWAYS guess the same letter, in every section. The distribution is pretty much total across an entire 5-section exam, so that it's 20% of each letter, and if you stick with the same letter consistently on your guesses, you'll get 20% of your guesses right. I'm also hoping that if you never finish a section you're always taking a minute at the end to fill in your guess letter on anything you haven't answered. For example, if you go in with your guess letter for the entire test being B, you should make sure before time runs out that anything you didn't get to has a B bubbled in, on every section.

vanwinkle wrote:I personally would quickly read each passage before I started the questions. Oh! I forgot something!

This is how your reading order should go:

1) Do the "read first two lines/glance at answers" thing to determine order of passages.

2) For each passage, when you start on it, read the questions first. Quickly read each question, to see if there's any important words or concepts to watch for while reading the passage.

3) Read the passage quickly, just fast enough to get the gist of it. You're not trying to understand everything right away, just to have an idea what the passage is talking about. Here, you should underline or mark anything that's clearly related to one of the questions you already read.

4) Pick the first question you're going to answer, read it again and read all the answers this time, and then go back to the passage to figure out what the answer is. Only reread the passage as much as you need to for the question you're on. Try to read to eliminate answer choices by finding things that make answers wrong, then when you're down to 2-3, find an effective way to pick one.

The process for an LG passage is kind of similar. You should take the first 60 seconds of the section to look at all the LG problems in the section, and visualize in your head what type they are. There's a clear pattern to LG, and the 3 easiest games should be something like this:

1)

Basic one-dimensional: Easiest will almost always be a one-dimensional problem, meaning you can solve it with a one-dimensional grid. For example (totally hypothetical, not plagiarized from anything LSAC owns at all), imagine the following problem:

Mary has seven students, Q, R, S, T, V, W, and Z, and seven appointments from noon to 6PM. Mary must make a schedule that fits all seven students into her schedule, and she can see no more than one student per hour. The following conditions apply to her students:

You're likely solving these as some kind of one-dimensional chart, like so:

Code: Select all

Time: 12 1 2 3 4 5 6

Question 1 Q Z R V W S T

Question 2 Q R V Z W T S

That's a one-dimensional chart. You can just create a graph to measure one dimension (time) and fill in your values (students) under each time to make a line. You can repeat this for each question. It's simple.

2)

Complex one-dimensional: Some tests have a harder one-dimensional as the second-hardest test; it might be the same kind of problem, but more complicated:

Mary has six students, Q, R, S, T, V, and W, and three appointments from noon to 2PM. Mary plans on teaching exactly two students per hour for each of the three hours. The following conditions apply to her students:

That might require a more complicated one-dimensional graph, where you have to keep track of two conditions at the same time:

Code: Select all

Time: 12 1 2

Question 1 Q,W V,S R,T

Question 2 Q,S R,W V,T

The "two at a time" is what makes it harder, because you're going to have to figure out more than one value for each slot, not just one. But still, it's a one-dimensional graph. Easy to draw, easy to figure out. If you start doing this one and then realize it's not the easiest one-dimensional graph, go ahead and finish it and then go do the easier one-dimensional one. If you have a test with two one-dimensionals (one basic and one complex like this) they're both unlikely to be the hardest.

3)

Two-dimensional: These require a huge graph for each question, and are more time-consuming and difficult. Do them after you've done all the one-dimensional ones. Here's an example of a two-dimensional one:

Pitt Railroad has three rail yards in Pennsylvania: Central, Pitt, and Scranton. Pitt Railroad stores four kinds of rail cars at these yards: boxcars, flat cars, grain cars, and tankers. Each yard stores more than one kind of railcar, but no yard stores all four kinds. All types of cars must be stored in at least one yard. The rail yards have the following conditions:

These are more of a pain in the ass. For each question you've got to graph out your answer in not just one but two dimensions, to figure out how many places you have each kind of car and where. Your graph might look something like this:

Code: Select all

Yard: Pitt Philly Central

B Yes Yes No

F No Yes No

G Yes No Yes

T No No Yes

And you have to make a whole new two-dimensional grid like that just to solve each problem. That's what makes it a two-dimensional problem.

The two hardest questions might both be two-dimensionals, if you're lucky. I say lucky because getting two one-dimensionals and two two-dimensionals means you've had a very standard LG section with no tricks or things to mess you up. Which brings us to the ones you should do last:

4)

"What-the-fuck" games: You know how to solve simple one-dimensional problems. You know how to solve advanced one-dimensional problems. You know how to solve two-dimensional problems. But sometimes you get to a problem and you just kind of stare at it for a minute, and go "Wait, how do I graph something like this?"

If you see this, turn and run back to the other three problems and do them all first. If you cannot easily tell how to graph it, that means it is bad news. You are probably going to have to draw some really awful and convoluted thing for each and every individual question, and it will take ten or fifteen minutes of your time just to figure out what the right kind of graph is, and you will be burning time figuring that out when you could be spending on the ones you already actually know how to solve. Run, just run. Run to the others, do them, and then come back and pick at this the best you can.

Here's an example of something you might see:

The state of Ames has five power grids, Grids 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. In order to power the entire state, each power grid must be connected to two of the other power grids. However, no grid may be connected solely to two grids that are connected to each other. The following conditions apply:

The first sentence might make you go, "Ooh! One-dimensional, I just have to write out 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and then just solve under it!" The second sentence (saying each grid is connected to two others) might make you go "Oh, it's complex one-dimensional, I've got to come up with two answers for each number." Then you read the third sentence and you go, "Wait... that means... how am I going to keep track of that easily? Is this two-dimensional?" You've got an extra variable (not just which grids

are connected but how that affects which others

can't) which makes graphing on an ordinary grid very, very difficult.

Maybe you try a one-dimensional graph:

Code: Select all

Grid: 1 2 3 4 5

Question 1 2,3 4,5 1,4 3,1 Wait, 4 is connected to 1 which is already connected to 2 and 3, and I put that 1 is connected to 2, but not that 2 is connected to 1, that means my graph isn’t helping me keep track of which ones can’t connect because they’re connected elsewhere already… damnit.

So you start trying to draw out a two-dimensional graph:

Code: Select all

Grid: 1 2 3 4 5

1 No No Yes No Yes

2 No No No Yes Yes

3 Yes No No No Yes

4 Wait… This graph isn't helping me keep track of which ones can't connect to which because they're already connected to each other. 1 is connected to 3 and 5, which means 3 and 5 can't both be connected together, but I can't tell that just by looking at the graph so I ended up putting 1, 3, and 5 all connected together... Damnit, this graph isn't helping me either!

This is what I like to call the "what-the-fuck" problems, because you just end up sitting there staring at them and going "what the fuck" instead of solving anything. You should always do these last, because even just figuring out how to graph them efficiently could take forever.

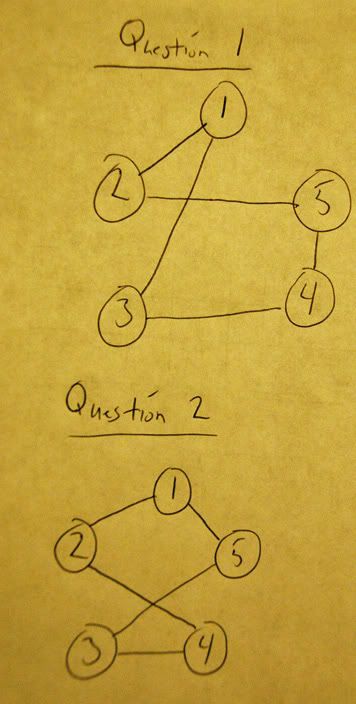

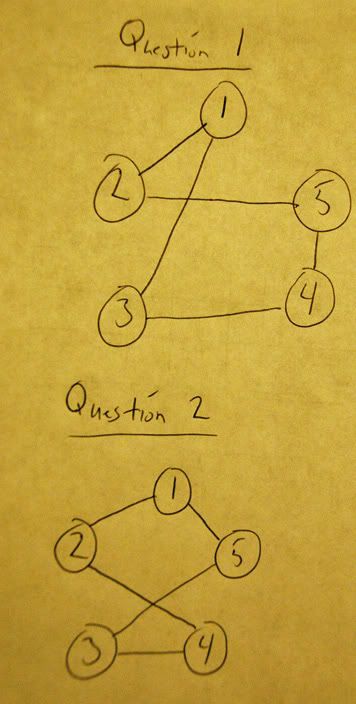

For the record, there is a way to graph this particular what-the-fuck problem, and it's by drawing a unique diagram for each question:

(Forgive the terrible handwriting, please.)

That kind of diagram shows you easily which are connected to which and you can trace them quickly to see which shouldn't be connected to which. The problem is that since it's not a normal way of diagramming, it'll take you time just to figure out how to diagram it, and that's time you could be spending answering the questions on the other sections.

So, with all those kind of games, just to recap, you should spend about 60 seconds looking through all the games in the LG section. All you're reading is the part of the setup like I quoted, just the first paragraph, and you stop at the "these are the following conditions" part. Don't read the conditions, they're not important yet. All you're doing right now is trying to visualize how you'd solve these problems. You're not actually drawing any graphs yet, just imagining how you would. If you practice doing this, you should be able to spot what kind of problem all four games are within 60 to 90 seconds. Then, you do the easiest one.

1)

One-dimensional problems (basic first, then complex, if you can tell the difference)

2)

Two-dimensional problems

3)

What-the-fuck problem

Not all tests will have a what-the-fuck problem, they might just have multiple two-dimensional problems first. But since one-dimensional problems can be done quicker you should still do them first anyway.